Eve Blouin

Eve Blouin“I do know that you could die twice. First comes bodily dying… to be forgotten is a second dying,” notes screenwriter Eve Blouin, in an epilogue on the finish of her mom’s autobiography.

Eve understands this sentiment greater than most.

Within the Fifties and 60s, her mom, the late Andrée Blouin, threw herself into the struggle for a free Africa, mobilising the Democratic Republic of Congo’s ladies towards colonialism and rising to turn out to be a key adviser to Patrice Lumumba, DR Congo’s first prime minister and a revered independence hero.

She traded concepts with famed revolutionaries like Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Guinea’s Sékou Touré and Algeria’s Ahmed Ben Bella, but her story is hardly identified.

In an try and treatment this injustice, Blouin’s memoir, titled My Nation, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, is being re-released, having spent a long time out of print.

Within the ebook, Blouin defined that her craving for decolonisation was sparked by a private tragedy.

She grew up between Central African Republic (CAR) and Congo-Brazzaville, which on the time had been French colonies named Ubangi-Shari and the French Congo respectively.

Within the Nineteen Forties, her two-year-old son, René, was being handled in hospital for malaria within the CAR.

René was mixed-race like his mom, and since he was one-quarter African, he was denied remedy. Weeks later, René was useless.

“The dying of my son politicised me as nothing else may,” Blouin wrote in her memoir.

She added that colonialism “was now not a matter of my very own maligned destiny however a system of evil whose tentacles reached into each section of African life”.

Blouin was born in 1921, to a 40-year-old white French father and a 14-year-old black mom from the CAR.

The 2 met when Blouin’s father handed via her mom’s village to promote items.

“Even in the present day, the story of my father and my mom, whereas giving me a lot ache, astonishes me nonetheless,” Blouin mentioned.

When she was simply three, Blouin’s father positioned her in a convent for mixed-race ladies, which was run by French nuns within the neighbouring Congo-Brazzaville.

This was widespread follow in France and Belgium’s African colonies – it’s thought that 1000’s of kids born to colonialists and African ladies had been despatched to orphanages and separated from the remainder of society.

Blouin wrote: “The orphanage served as a type of waste bin for the waste merchandise of this black-and-white society: the kids of combined blood who match nowhere.”

Eve Blouin

Eve BlouinBlouin’s expertise within the orphanage was extraordinarily detrimental – she wrote that the kids on the establishment had been whipped, underfed and verbally abused.

However she was headstrong – she escaped from the orphanage aged 15 after the nuns tried to drive her into marriage.

Blouin ultimately married by her personal will, twice. After René’s dying, she moved together with her second husband to Guinea, a West African nation which was additionally ruled by the French.

On the time, Guinea was within the midst of a “political tempest”, she wrote. France had promised the nation independence, but additionally required Guineans to vote in a referendum on whether or not or not the nation ought to preserve financial, diplomatic and navy ties with France.

The Guinean department of the pan-African motion the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA) wished the nation to vote “No”, arguing that the nation wanted whole liberation. In 1958, Blouin joined the marketing campaign, driving all through the nation to talk at rallies.

A 12 months later, Guinea secured its independence by voting “No” and Sékou Touré, Guinea’s RDA chief, turned the nation’s first president.

By this level, Blouin had begun to develop appreciable clout in post-colonial, pan-African circles. She wrote that after Guinea turned unbiased, she used this affect to advise the CAR’s new President Barthélemy Boganda, persuading him stand down in a diplomatic row with Congo-Brazzaville’s post-independence chief, Fulbert Youlou.

However counselling was not all Blouin needed to provide this fast-changing Africa.

In a restaurant in Guinea’s capital, Conakry, she met a gaggle of liberation activists from what would later turn out to be DR Congo. They urged her to assist them mobilise Congolese ladies within the struggle towards Belgian colonial rule.

Blouin was pulled in two instructions. On one hand, she had three younger youngsters – together with Eve – to boost. On the opposite, “she had the restlessness of an idealist with a sure anger on the world because it was”, Eve, now 67, instructed the BBC.

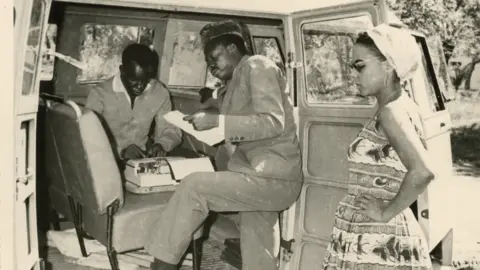

In 1960, with Nkrumah’s encouragement, Andrée Blouin flew alone to DR Congo. She joined outstanding male liberation activists, corresponding to Pierre Mulele and Antoine Gizenga, on the street, campaigning throughout the nation’s 2.4 million sq km (906,000 sq miles) expanse. She reduce a hanging determine, travelling via the bush together with her coiffed hair, form-fitting clothes and stylish, translucent shades.

Eve Blouin

Eve BlouinIn Kahemba, close to the border with Angola, Blouin and her workforce paused their marketing campaign to assist construct a base for Angolan independence fighters who had fled from the Portuguese colonial authorities.

She addressed crowds of ladies, encouraging them to push for gender equality in addition to Congo’s independence. She additionally had a knack for organising and technique.

Quickly, the colonial powers and worldwide press caught wind of Blouin’s work. They accused her of being, amongst many issues, Nkrumah’s mistress, Sékou Touré’s agent and “the courtesan of all of the African chiefs of state”.

She attracted much more consideration when she met Lumumba.

In her ebook, Blouin describes him as a “lithe and chic” man whose “title was written in letters of gold within the Congo skies”.

When the nation clinched its independence in 1960, Lumumba turned its first prime minister. He was simply 34 years previous.

Lumumba chosen Blouin as his “chief of protocol” and speechwriter. The pair labored collectively so intently that the press dubbed them “Lumum-Blouin”.

Blouin was described by the US’s Time journal as a “good-looking 41-year-old” whose “metal will and fast power make her a useful political aide”.

However a slew of disasters struck workforce Lumum-Blouin – and the newly fashioned authorities – only a few days into their tenure.

Firstly, the military revolted towards their white Belgium commanders, sparking violence throughout the nation. Then, Belgium, the UK and US backed secession in Katanga, a mineral-rich area that every one three Western nations had pursuits in. Belgian paratroopers swooped again into the nation, supposedly to revive safety.

Blouin described the occasions as a “conflict of nerves”, with traitors “organising all over the place”.

Herbert Weiss

Herbert WeissShe wrote that Lumumba was a “true hero of recent occasions”, but additionally admitted she thought he was naïve and, at occasions, too delicate.

“It’s true that those that are of the most effective religion are sometimes probably the most cruelly deceived,” she mentioned.

Inside seven months of Lumumba taking cost, military chief of workers Joseph Mobutu seized energy.

On the 17 January Lumumba was assassinated by firing squad, with the tacit backing of Belgium. It’s attainable the UK was complicit, whereas the US had organised earlier plots to kill Lumumba – fearing that he was sympathetic to the Soviet Union throughout the Chilly Battle.

In her ebook, Blouin mentioned the shock and grief brought on by Lumumba’s dying left her speechless.

“By no means earlier than had I been left with out torrents of issues to say,” she wrote.

She was residing in Paris on the time of the killing, having being compelled into exile after Mobutu’s coup.

To make sure Blouin wouldn’t speak to the worldwide press, the authorities made her household – who had moved to Congo – keep within the nation as “hostages”.

The separation was crushing for Blouin, who, as Eve describes, was “very protecting” and “very maternal”.

Reflecting on her mom’s persona, Eve provides: “One would not wish to antagonise her as a result of despite the fact that she had an enormous and beneficiant coronary heart, she may very well be quite unstable.”

Whereas Blouin was in exile, troopers looted her household house and brutally beat her mom with a gun, completely damaging her backbone.

Blouin’s household had been lastly capable of be part of her after months of separation.

They spent a short interval in Algeria – the place they had been provided sanctuary by the nation’s first post-independence President, Ahmed Ben Bella.

They then settled in Paris. Blouin remained concerned in pan-Africanism from afar “within the type of articles and nearly each day conferences”, Eve wrote within the memoir’s epilogue.

Herbert Weiss

Herbert WeissWhen Blouin started writing her autobiography within the Nineteen Seventies, she nonetheless had nice reverence for the independence actions she had devoted herself to.

She had excessive reward for Sékou Touré, who by that time had established a one-party state and was ruthlessly suppressing freedom of expression.

Blouin did nonetheless develop deeply despondent that Africa had not turn out to be “free”, as she had hoped.

“It’s not the outsiders who’ve broken Africa probably the most, however the mutilated will of the individuals and the selfishness of a few of our personal leaders,” she wrote.

She grieved the dying of her dream, a lot in order that she refused to take remedy for the most cancers that was ravaging her physique.

“It was horrible to look at. I used to be completely powerless,” Eve mentioned.

Blouin handed away in Paris on 9 April 1986, on the age of 65. In keeping with Eve, her mom’s dying was met by the world with “dreary indifference”.

She stays an inspiration in some corners, nonetheless. In DR Congo’s capital, Kinshasa, a cultural centre named after Blouin provides the likes of instructional programmes, conferences, and movie screenings – all underpinned by a pan-African ethos.

And thru My Nation, Africa, Blouin’s extraordinary story is being launched for a second time, this time right into a world that reveals larger curiosity within the historic contributions of ladies.

New readers will be taught of the woman who went from being stashed away by the colonial system, to combating for the liberty of tens of millions of black Africans.

My Nation, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, revealed by Verso Books, goes on sale on 7 January within the UK

You may additionally be curious about:

Getty Pictures/BBC

Getty Pictures/BBC